“Plug and Play” Programming: Being Open to Variation

When I first got into strongman in 2007-2009, most of the content I could find and consume were articles on big sites like Elitefts and T-nation. It did not take long to come across various ways to use conjugate style programming for strongman. The underlying principle for this style of training was using variations of movement, intensity, and speed to keep the athlete fresh and meet contest tested demands. Westside Barbell was one of the most popular at the time for using this method, so most of strongman programming at the time seemed to mirror their use of max effort and dynamic effort days, only subbed for strongman specific movements.

Now that we have an idea of where the idea of variation came from, we have to understand why we might use variation. For the sake of this article, I am going to touch on the use of variations to improve form or movement patterns and to bring up a “weak area”.

Weightlifters are a great example of using subtle variations and partial lifts to target specific traits or skills needed in the execution of the contested lifts. Often we see the contested lifts of the snatch and clean and jerk broken up into parts. Focuses on pulls, from a hang or blocks, just the clean, just the jerk, different complexes and press styles. From this it became very apparent to me that to bring about improvement and increase skill, the movement had to have a very intentional focus and not be cluttered by doing too many “parts”.

On the other hand, the idea of improving a weak area can be seen from different points of view. Often in Westside programming, the higher rep accessory work was in place to bring up lagging muscle groups and their relative strength. While this is definitionally warranted, I really want to touch on the bigger idea of the variations being used to improve the motor pattern or target the weak area from a movement perspective. If an athlete had a deficit, much like weightlifting, Westside often programmed main lifts that the deficit was the limiter or that more time was spent in a vulnerable position to strengthen the deficit. This furthermore helped me to understand the application of variations for more than just being novel or keeping an athlete fresh.

So what does this have to do with the idea of “plug and play”. What I mean by this title is having areas of the training that are not necessarily programmed in stone but have flexibility to plug in for the variation needed at the time to best get the outcome for the greater training plan. You might think, “so we just train conjugate like Westide?”. Not exactly.

The way I view this style of training is having guidelines or limits in place that guide how much volume or intensity while being open to changing select movements based on movement quality on the week prior to prime, improve, on better engrain movement patterns. Let us look at an example of how I might use this to better understand.

Let us say we are running a fairly basic linear progression for strict press from the rack (because we can view the clean as a separate movement for programming) and we want to be able to have the opening of using variation to improve a lagging area. Our original plan is similar to something below:

Week 1: 3x8 at 60% (RPE 6-7)

Week 2: 3x8 at 65% (RPE 7)

Week 3: 4x6 at 70% (RPE 7)

Week 4: 4x6 at 75% (RPE 7.5)

Week 5: 4x5 at 77.5% (RPE 8)

Week 6: 3x5 at 80% (RPE 8)

Week 7: 4x4 at 82.5% (RPE 8-8.5)

Week 8: 6-8RM (RPE 10)

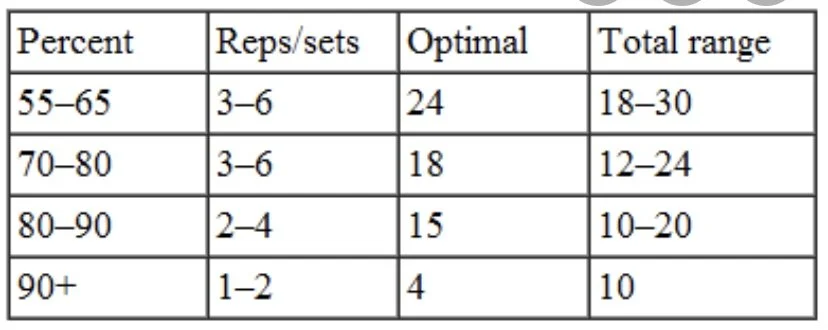

If you follow the overall volume, we have 24 reps total for 4 weeks, then 20 reps, then 15-16 reps, then a max. If we are familiar with Prilepin’s Chart, we will see that pretty much every week falls into the optimal volume for the percentage given. This chart is very helpful in understanding the cap of reps at various percentages.

With these guidelines, we can use “plug and play” to better allocate that volume to other variations that could help the long term progress of the program. Let me give some examples.

Week one starts off well but we notice that the athlete lacks power off the shoulders and is either trying to bounce or cut range of motion. Week two calls for 3x8 but with all the reps being done on strict press without any variation. Instead of just rolling with the program and hoping the weakness will just iron out over time, we can shift volume to a movement that we know will progress that weakness.

Week two could become 2x8 at 65% then 1x8 with 3ct pause at the shoulder, dropping say 10% load to accommodate for the difficulty increase and keep roughly the same intensity (RPE) as the two sets prior. We might decide to use a pin press and have the bar rest on the pins and have each rep from a dead stop. This could be for 1x8 or even 2x4 or 3x3 (9 reps but close enough). The idea is to have the same total reps at the same intensity.

Now we move to week three. We could continue to leverage the variation we used and now increase to two sets on the variation, since we have four sets to work with. Or, maybe, the prior week and feedback gave better intent to the athlete and the issue has somewhat been corrected. In that case, we can continue along with the plan of a straight forward 4x6.

The cool thing here with using variation is the variations we mentioned above in this case will need less load but be just as intense. So while we meet the same rep total of 24 reps, we actually have less load on the joints, in theory, since the variation is using less load to accomplish the same intensity level as the straight sets. This makes this idea of “plug and play” not only helpful for improving a weak area but also something we can leverage to stay healthy or reduce fatigue (heavily dependent on variation selected as lesser range of motion often comes with increased loads) as the load could be less.

So you may be asking, “what variations should I use?” Unfortunately, that is very case dependent and too much for this article but to sum up the goal, expose what you need to work on more. You would not expect to get better at math by avoiding doing all math (cue meme of this generation needing a phone calculator for addition). If we want to get more comfortable with the depth in a squat, leg drive in a press, or hyperextension in a loading event we need to spend time there. Think of it as building a “relationship” with the movements. No range of motion or movement pattern is ever going to “love” you if you never come around. And if you hate a movement, well, learn to “love” it.

Once you have experimented and have your variations that you know you need to work on you have the power to leverage any program, even if the overarching principle is a linear or block style programming method. The variations do not need to be complex. They can be as subtle as an added tempo, band, chains, or changing range of motion slightly. Remember, weightlifters vary a movement by as little as a hang from mid quad to just above the knee. It can be a change as small as a 1-2” deficit.

Now, I know some of you are afraid of “going off programming”. As a coach, I understand and do not necessarily recommend doing this if working with a professional coach. However, my viewpoint as a coach with my athletes is fixing the issues as soon as I can. I do not just want to give them a hammer and hope after enough swings we built a house. If a small change of movement can better cue, prime, or help them just “learn” how to move better I am all for it. And guess what? This strategy can be as short term or as long term as deemed appropriate. The athlete does not know how to get in a good position rep to rep? Use some volume one week to have them do a controlled eccentric, they figure it out, and next week we no longer need to use it. Or maybe we use it in warm ups to a certain percentage and gradually over time decrease the percentage before dropping it entirely. As always, there are some many effective ways to program.

In summary, I hope this brief article gives you a better understanding on how to empower your programming by the use of variation. We do not necessarily need to go all in on a conjugate style program to reap the benefits from the underlying principles. While a lot of the programming questions might still come with everyone’s least favorite answer of “it depends on the athlete”, remember not to be afraid to try something new. Everything in the gym is learning. What works, what does not work, what worked and now does not work. Continue to evolve your programming and use “plug and play” as needed to accomplish that.